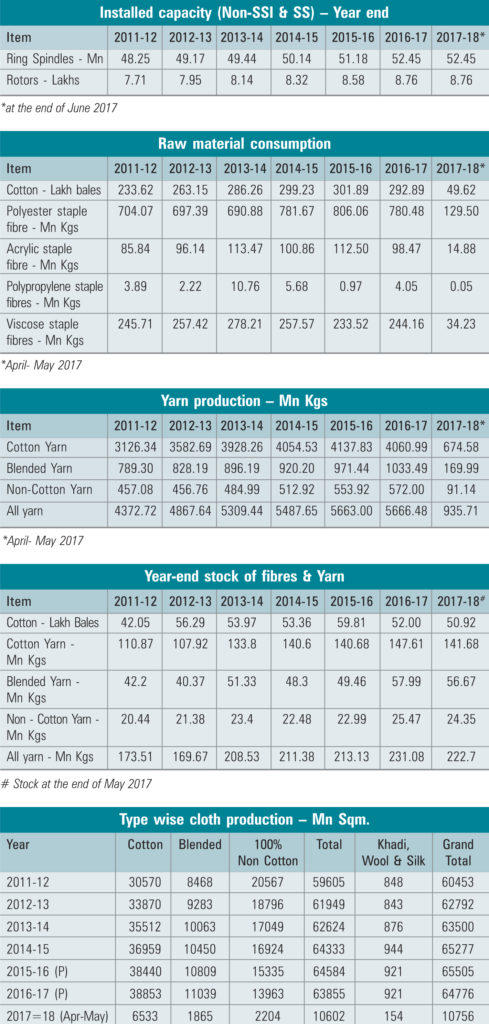

Much has been said and written about the dire need to make our textiles and clothing (T and C) sector globally competitive in the man-made fibre (MMF) segment. This is because our presence in the MMF-based garment segment is very limited, notwithstanding the enormous scope. Moreover, the usage of synthetic fibre is more than that of cotton which is the prevailing practice worldwide. The ratio is 60:40, whereas in India it is 43:57. The government recognises this stark reality, but has not initiated appropriate action in this regard. The 2017-18 budgets have provided no duty reliefs for MMFs. That would have helped the T and C sector to use more synthetic fibres for garment production and for export and reduce dependence on cotton, a natural fibre. The introduction of Goods and Services Tax (GST) has not helped. The rates for MMFs need a scaling down, atleast for yarns.

While there is no serious move to remedy the situation, the bitter truth is that the country may witness saturated levels in the textile value chain (barring value addition). This underscores the need for the T and C sector to become globally competitive in the synthetic segment across the value claim. In the absence it will be a far cry to achieve the projected textile business size of $350 bn from the current $208 bn and creation of 22 mn new jobs by 2025.

At home the industry is already suffering several disadvantages – 23 per cent to 30 per cent expensive synthetic raw materials, high interest and power costs. Then the industry faces a 9.6 per cent to 20 per cent import duty in the entire global market, free trade agreement with neighbouring countries such as Bangladesh.

On MMFs, the considered view of South India Mills Association (AIMA) and conveyed to the Finance Ministry is that the 18 per cent GST rate on yarns and 5 per cent rate on fabrics leads to inverted duty problem and adds to cost, since refund of accumulated tax credit is not allowed at the fabric stage. There is no revenue loss with a 12 per cent GST on MMF and its blended spun yarn and also value-added filament yarns like sewing threads.

At the same time, it is necessary to take safeguard measures to protect the domestic industry from cheaper imports of yarns and fabrics from neighbouring countries and China. The measures should include raising the import duty or levying additional customs duty on yarn and fabrics. Again, the rules of origin, including yarn and fabric forward rule should be imposed on imports.

It may not be relevant in the context of implementation of GST. But SIMA has raised the question of liberal export benefits under the Duty Drawback Scheme, Refund of State levies (ROSL), Merchandise Exports from India Scheme (MEIS) and Interest Equalisation Scheme (IES).In order to create a level playing field for the industry in the global market.

There is vast scope for increasing consumption of MMFs in the country, since the share of MMF products in the total textile production is considerably lower than that of world average. In fact, the share of MMF products in exports is even lower than that of total textile production.

As is known, our current reputation in the global market is basically only as an efficient supplier of fibre yarn, and filament fabrics. Our presence in the final products of garments and made-ups is limited. Globally, India ranks second in man-made fibre filament yarn production. It has a 12 per cent share of global production of cellulosic fibre and filament and 7 per cent in synthetic fibres and filaments. India’s capacity for MMFs and filament yarns now stands around 4 bn kg which is 7 per cent of global capacity. Total production of MMFs and filament together stood at 2,600 mn kg during 2013-14 of which exports constituted around 32 per cent at 827 mn kg of domestic consumption. The MMF industry is largely polyester dominated, which constitutes about 82 per cent of its total production.

Installed capacity and production of viscose fibre is much higher than domestic production. This means increased availability for exports. Domestic consumption is 75 per cent of production and the rest is exported. But opposite is the case for viscose filament yarn. And import of viscose filament yarn is significantly higher than domestic consumption.

Installed capacity and production of viscose fibre is much higher than domestic production. This means increased availability for exports. Domestic consumption is 75 per cent of production and the rest is exported. But opposite is the case for viscose filament yarn. And import of viscose filament yarn is significantly higher than domestic consumption.

There is no difference in technology or skills required for cotton and MMF products. The difference is in the cost competitiveness of fibres. Fibre neutral policies promised by the government are yet to be implemented. It would have ameliorated the situation, albeit partly. Increased profit for MMF would retard textile production. The balance between the two should be properly assessed before duties are imposed on MMF, instead of seeking imports that will only destroy domestic production.

India has failed to grab the opportunity to increase its global market share in 1995, when China was facing problems on the production front due to high costs, coupled with environmental issues. The time is now ripe for the government and the industry to scale up production facilities to increase textile production. A pre-requisite for this is diversifying into the MMF segment.

The brief opportunity was thrown up in 1995 when the phasing of bilateral quotas had started. But the garment manufacture was reserved for the small scale sector for ten more years. At the same time, migration of fibre production from the organised sector to the decentralized sector was permitted. And no concerted efforts were made for investing in capacity building during the first few years of the quota period.

To conclude, immediate policy intervention is required by the government to facilitate the T and C sector to make its presence for MMFbased garment segment felt more in the global market than at present.